The Allergic March

The allergic march, aka the atopic march, is a concept describing the possible progression of allergies in your child. Allergic diseases are usually multi-system in nature, so it is not uncommon for infants with eczema to go on to develop one or more of food allergy, asthma, hay fever, and oral allergy syndrome. Whilst this is true at a study population level, it is very hard to predict the likely course for each child.

Whilst it’s not possible to alter any genetic predisposition, it does make sense to minimise the risk of progressing along this march through modifying environmental factors.

The two most significant disease-modifying interventions are the best eczema control and the introduction of common and relevant food allergens for your child. Healthy living strategies will help nurture the gut and skin microbiomes, so these seem prudent as well.

It may be that early mite and pollen immunotherapies may decrease allergic respiratory disease, but such studies remain under investigation.

Pollution and mould are harmful for all lungs, allergic and non-allergic alike, so steps to reduce them, e.g., air purifiers in bedrooms, seem wise.

As with asthma, there are many ‘eczemas’ - severe eczema, oozing, wheeping, crusting, staph-infected, and which are often on exposed skin areas (hands, feet, face, head and neck) seem to be most strongly associated with the development of food allergy, so early and proactive treatment of this is warranted.

We have separate posts regarding optimising skin control, restoring the gut biome and early weaning, so if the topic is of interest or concern to you, please read those as well.

What Is the Allergic March?

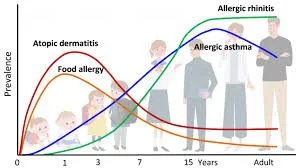

There is some data to support a typical progression of allergic diseases in childhood: starting with atopic dermatitis (eczema) and food allergies in infancy, transitioning to wheezing, asthma, and allergic rhinitis in later childhood and adolescence, with some conditions (like eczema) often remitting over time.

However, the Allergy March is not universal or linear. There is significant individual variability in trajectories, influenced by genetic predispositions, environmental exposures (e.g., microbiome, pollutants), and immunologic factors.

Not all children follow the typical sequence; some skip stages, and others may have persistent or atypical patterns. So please do contact us if you wish for a detailed assessment of your child's existing allergies and ways in which we may be able to treat and prevent additional allergies from developing.

Worried About Allergies? Let’s Help You Get Answers

If your child is showing signs of a food, pollen, or skin allergy, early diagnosis is key. At London Allergy Consultants, our expert team provides trusted, evidence-based care tailored to your child’s needs. From testing to treatment plans, we guide you every step of the way.

London Allergy Consultants

London Allergy Consultants is a leading UK centre for diagnosing and treating food and airborne allergies in children and young people.

Sesame Oral Immunotherapy (OIT) has emerged as a Sesame Oral Immunotherapy (OIT) has become a medical therapy for children with severe sesame allergies. Unlike simple avoidance, OIT aims to retrain the immune system by allowing the regular, supervised consumption of small amounts of sesame protein.